El Niño-Southern Oscillation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

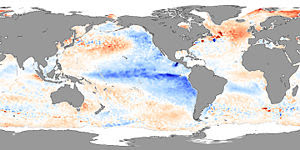

El Niño-Southern Oscillation is a periodic change in the atmosphere and ocean of the tropical Pacific region. It is defined in the atmosphere by changes in the pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin, Australia, and in the ocean by warming or cooling of surface waters of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. El Niño is the name given to its warm phase of the oscillation -- the period when water in that region is warmer than average. La Niña is the name given to the cold phase of the oscillation, or the period when the water in the tropical Eastern Pacific is colder than average. The oscillation has no well-defined period, but instead occurs every three to eight years. Mechanisms that sustain the El Niño-La Niña cycle remain a matter of research.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation is often is abbreviated in scientific jargon as ENSO and in popular usage is commonly called simply El Niño. The name is Spanish for "the boy" and refers to the Christ child, because periodic warming in the Pacific near South America is usually noticed around Christmas. Conversely the name for the cool phase of the oscillation, "La Niña," is Spanish for "the girl."

El Niño is associated with floods, droughts and is linked to other weather disturbances in many locations around the world. El Niño's effects in the Atlantic Ocean lag behind those in the Pacific by 12 to 18 months. Developing countries dependent upon agricultural and fishing are especially affected. El Niño's effects on weather vary with each event. Recent research suggests that treating ocean warming in the eastern tropical Pacific separately from that in the central tropical Pacific may help explain some of these variations.

Definition

Climate scientists define El Niño and La Niña based on sustained differences in Pacific-Ocean surface temperatures when compared with the average value. The accepted difference is anything greater than 0.5C (or 0.9F) averaged over the east-central tropical Pacific Ocean. When this happens for less than five months, it is classified as El Niño or La Niña conditions; if the anomaly persists for five months or longer, it is called an El Niño or La Niña "episode."[5] Typically, this happens at irregular intervals of 2–7 years and lasts nine months to two years.[6]

The first signs of an El Niño are:

Rise in surface pressure over the Indian Ocean, Indonesia, and Australia

Fall in air pressure over Tahiti and the rest of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean

Trade winds in the south Pacific weaken or head east

Warm air rises near Peru, causing rain in the northern Peruvian deserts

Warm water spreads from the west Pacific and the Indian Ocean to the east Pacific. It takes the rain with it, causing extensive drought in the western Pacific and rainfall in the normally dry eastern Pacific.

El Niño's warm current of nutrient-poor tropical water, heated by its eastward passage in the Equatorial Current, replaces the cold, nutrient-rich surface water of the Humboldt Current. When El Niño conditions last for many months, extensive ocean warming occurs and its economic impact to local fishing for an international market can be serious.

Early stages and characteristics of El Niño

Although its causes are still being investigated, El Niño events begin when trade winds, part of the Walker circulation, falter for many months. A series of Kelvin waves—relatively warm subsurface waves of water a few centimeters high and hundreds of kilometers wide—cross the Pacific along the equator and create a pool of warm water near South America, where ocean temperatures are normally cold due to upwelling. The Pacific Ocean is a heat reservoir that drives global wind patterns, and the resulting change in its temperature alters weather on a global scale. Rainfall shifts from the western Pacific toward the Americas, while Indonesia and India become drier.

Jacob Bjerknes in 1969 helped toward an understanding of ENSO, by suggesting that an anomalously warm spot in the eastern Pacific can weaken the east-west temperature difference, disrupting trade winds that push warm water to the west. The result is increasingly warm water toward the east. Several mechanisms have been proposed through which warmth builds up in equatorial Pacific surface waters, and is then dispersed to lower depths by an El Niño event. The resulting cooler area then has to "recharge" warmth for several years before another event can take place.

While not a direct cause of El Niño, the Madden-Julian Oscillation, or MJO, propagates rainfall eastward around the global tropics in a cycle of 30–60 days, and may influence the speed of development and intensity of El Niño and La Niña in several ways.For example, westerly flows between MJO-induced areas of low pressure may cause cyclonic circulations north and south of the equator. When the circulations intensify, the westerly winds within the equatorial Pacific can further increase and shift eastward, playing a role in El Niño development. Madden-Julian activity can also produce eastward-propagating oceanic Kelvin waves, which may in turn be influenced by a developing El Niño, leading to a positive feedback loop.

Effects of ENSO's cool phase (La Niña)

La Niña is the name for the cold phase of ENSO, during which the cold pool in the eastern Pacific intensifies and the trade winds strengthen. The name La Niña originates from Spanish, meaning "the little girl", analogous to El Niño meaning "the little boy". It has also in the past been called anti-El Niño, and El Viejo (meaning "the old man").

North America

Regional impacts of La Niña.

La Niña causes mostly the opposite effects of El Niño. Atlantic tropical cyclone activity is generally enhanced during La Niña. La Niña causes increased rainfall across the United States' Midwest. Other potential impacts include above average precipitation in the Northern Rockies, Northern California, and in southern and eastern regions of the Pacific Northwest. Below-average precipitation is expected across the southern tier, particularly in the southwestern and southeastern states."

In Canada, La Nina will generally cause a cooler, snowier winter, such as the near record-breaking amounts of snow recorded in the La Nina winter of 2007/2008 in Eastern Canada.

Asia

During La Niña years, the formation of tropical cyclones, along with the subtropical ridge position, shifts westward across the western Pacific ocean, which increases the landfall threat to China. In March 2008, La Niña caused a drop in sea surface temperatures over Southeast Asia by an amount of 2°C. It also caused heavy rains over Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia.

by : Dielanova Wynni Yuanita

XG / 7